Shorts

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

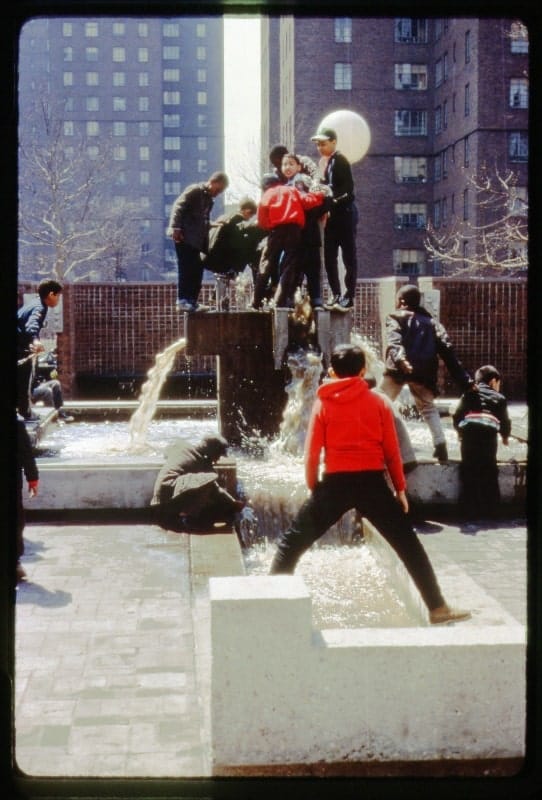

M. Paul Friedberg (New York Times)

Landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg of MPFP passed away last month. His obituary in the New York Times celebrates his contributions to the landscapes of play:

He was inspired by the adventure playgrounds springing up in Europe, where designers had observed children playing in the rubble after World War II. “They realized children really didn’t need formal play environments,” Mr. Friedberg told The New York Times in 1999. “They gave children saws and drills and boxes and called them adventure playgrounds.”

His playscapes are notable for their sheer potential, inviting imaginative uses by children as well as adults. Built in 1965, Riis Park Plaza was a masterpiece, a series of pyramids and stacked volumes for sitting, climbing, running, and jumping that formed an amphitheater, a fountain, a garden, and a playground, each a dedicated space flowing into its neighbors with considered connections. With their inherent sculptural beauty—much like Noguchi’s play equipment—these structures might be better considered landscape design in general rather than playgrounds.

The playable city is a livable city; making environments that are safe, fun, and stimulating for children pays off for everyone. The plaza at the center of the Riis Houses in the East Village has since reverted to fenced-off lawns and standardized play equipment. Friedberg speaks of our tendency to push away out natural inclinations toward creativity and play, and leaves us with this:

There are people whose whole life is dedicated to play, and those are the people we call artists.

Camille Henrot (Hauser & Wirth)

One of my favorite artists, Camille Henrot, has opened her first major New York solo exhibition with Hauser & Wirth this winter. More than a decade ago in Venice, she won the Silver Lion for Grosse Fatigue (2013), a film that gave form to our experience of knowing and feeling after finitude in the internet age; it still rings true, and the conditions it speaks to have only accelerated since.

The current New York exhibition, “A Number of Things,” is cool because it allows us to stick with the theme of playground design. Working with the architects Charlap Hyman & Herrero, she has covered the gallery floor with the thick rubber surface that so often undergirds outdoor play structures, a little bit squishy and a little bit bouncy, ready to absorb broken elbows and damaged egos. Here, the playground consists of sculptures in bronze. The most imposing works, from the “Abacus” series, quote the bead mazes of generic waiting rooms in hospitals, offices, and preschools, bringing them to a heroic scale and materiality while also making them a bit sharper, a bit dangerous—more formally interesting. Other works tame the modernist heritage by turning its artifacts into a pack of dogs on leads tied up at the edge of the park. Play is made serious, even critical, while the self-serious is allowed to feel fragile.

In her interview with Artnet, Camille echoes Paul Friedberg almost exactly:

Playing is how we train for life. Not to mention the fact that there is also a huge liberatory power in play. … Between “A Number of Things” worth figuring out is how and when we came about to divorce play from the imagination.

She is also profiled in Frieze and reviewed in the New York Times.

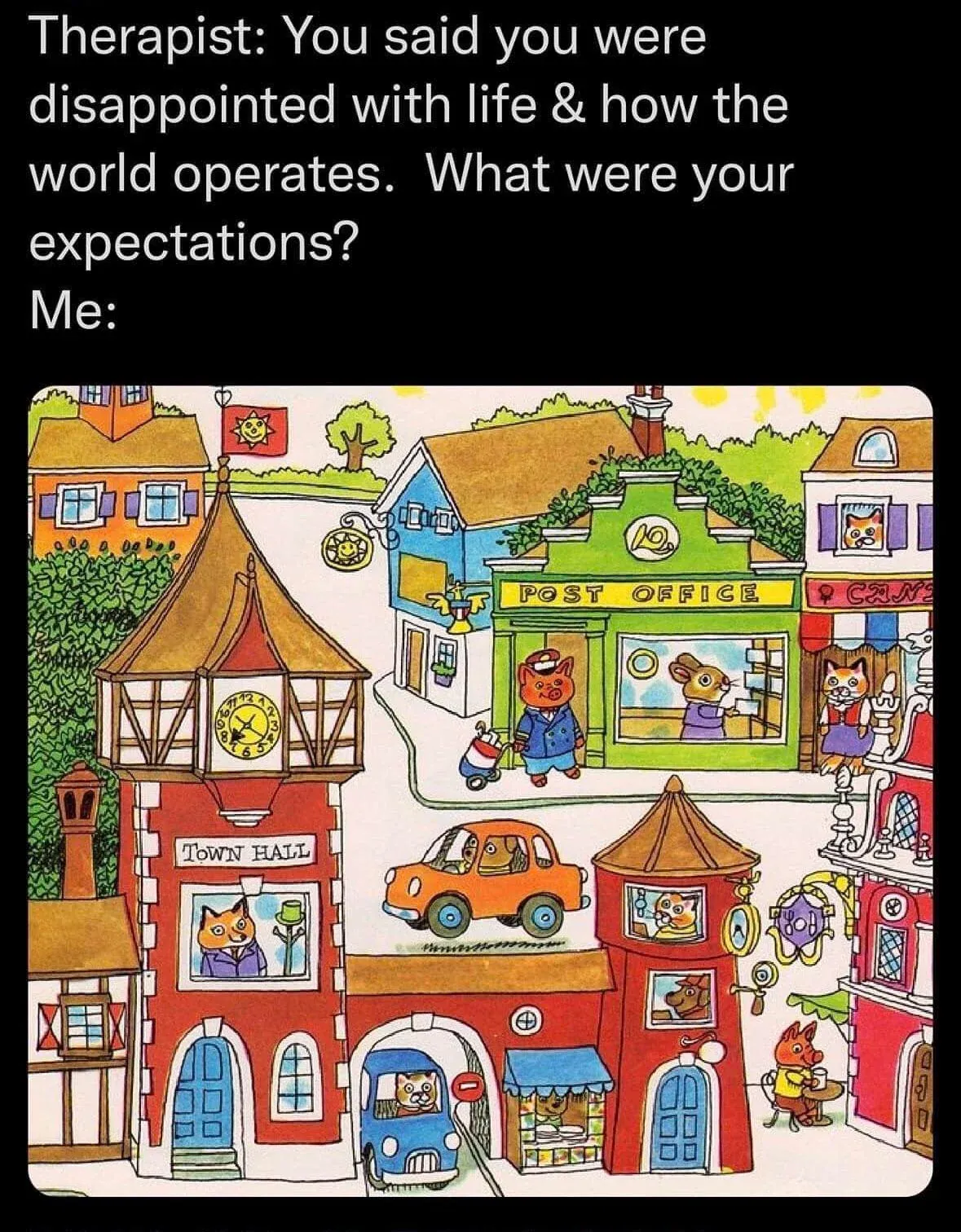

Chris Ware on Richard Scarry (The Yale Review)

Chris Ware is one of our preeminent graphic novelists, and the man responsible for the most epic New Yorker covers. In the Yale Review (which has become a sleeper hit under the editorship of Meghan O’Rourke over the last five years), he has an essay marking the 50th anniversary of Richard Scarry’s Cars and Trucks and Things That Go. Scarry’s graphic dispatches from Busy Town form the texture of childhood for my generation, to the point that there is a well-known meme that is continually making the rounds:

In his essay, Chris sketches out Richard Scarry’s biography, and the happy series of steps that led to the creation of the Busytown expanded universe. Importantly, Scarry spent the Second World War as an art director across Europe and North Africa, later ultimately moving permanently to Lausanne and Gstaad, where he drew the Busytown books:

Scarry’s guides to life both reflected and bolstered kids’ lived experience and in some cases, like my own, even provided the template for it. And while often sweet and quiet in its depiction of a picture-perfect society functioning measuredly—was Busytown urban or suburban or . . . European? (Where did all those Tudor homes and corner groceries come from, anyway?)—there’s just enough innocent mayhem and tripping and falling to hint at a darker side of things, like failing 1970s marriages and the things on television news that adults were always yelling about.

A decidedly un-American tone runs through much of it. By “un-American” I don’t mean anti-American. Instead, I mean there’s a top-down, citizen-as-responsible-contributor, sense-of-oneself-as-part-of-something-bigger that feels, well, civilized.