Essay

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

Portraiture for me has become a practice of autofiction. When I started my career, I was obsessed with technology and bored by painting. I was undereducated and under-informed, and have only learned a little bit since then. A lot of my writing and thinking in the first decade of my career was on what we called post-internet art, which Karen Archey and I defined as contemporary art “consciously created in a milieu that assumes the centrality of the network.” A key point of reference for us was David Joselit’s idea of painting beside itself; I remember Karen telling me about a dream in which she titled an exhibition “Everything Beside Itself.” Up to a certain moment, the only painting that made sense to me was conceptual in nature, playing with the codes of digital culture to make painting about its own production. Following David: Jutta Koether, Wade Guyton, Seth Price. Serious and impersonal painting.

Through approaches to portraiture like Celia Paul’s, I have slowly come to understand how every painting stands beside itself, how the social diagram of the production of art is actually visualized in many kinds of painting, if not most, and acknowledging this reality is, in fact, one of the primary directives of looking at and talking about art. In her current exhibition in London, Celia recomposes a famously staged photograph of Lucien Freud, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, and Michael Andrews out to lunch in Soho in 1963. This is not a biographical anecdote. This is painting fully beside itself. There is zero distance between Celia’s Colony of Ghosts and Jana Euler’s “GWF (Great White Fear)” paintings.

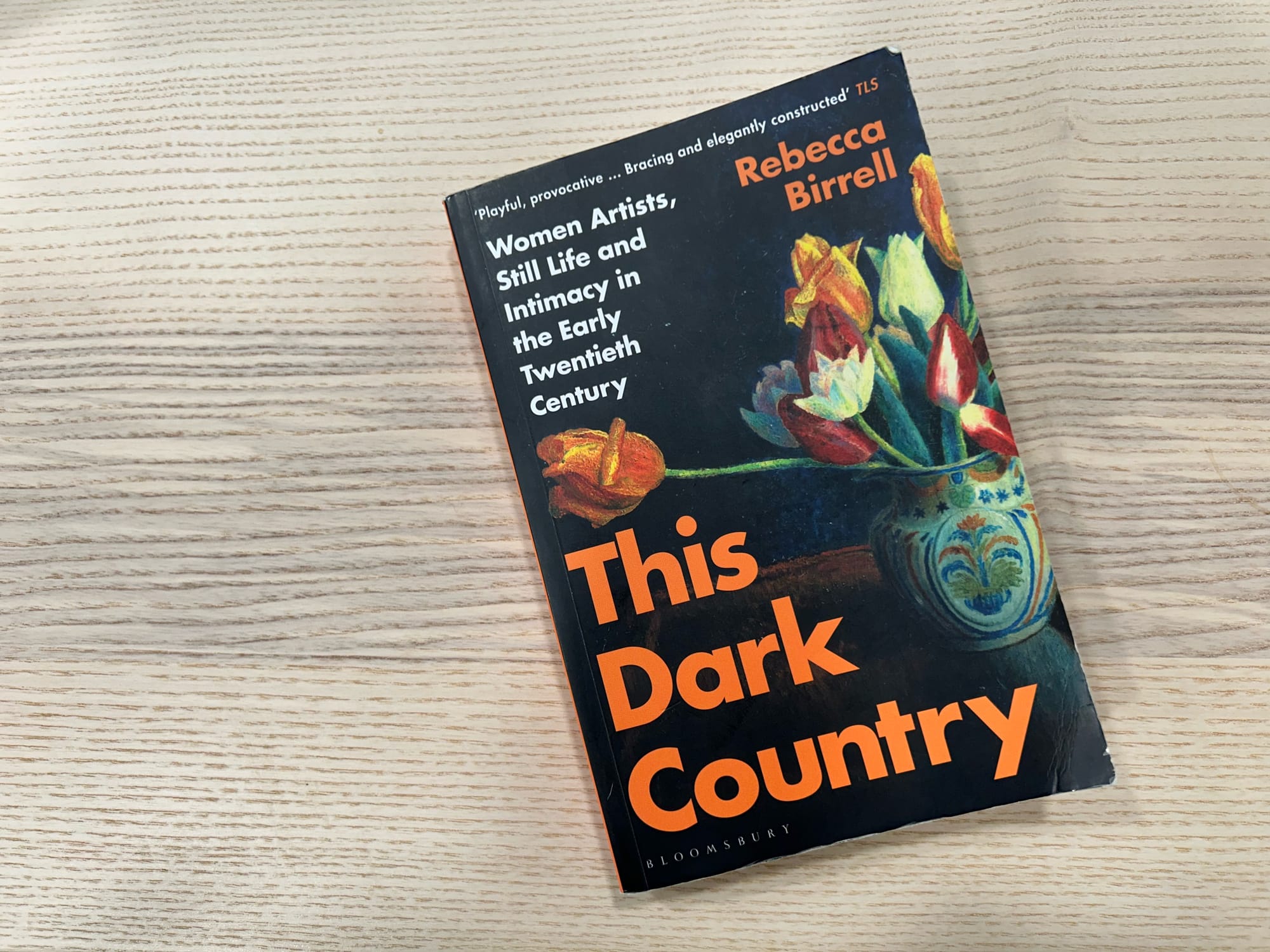

At the London Review Bookstore a few years back I picked up a copy of This Dark Country, a striking book by the curator and scholar Rebecca Birrell that has become enormously important to me. Subtitled Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century, it is something of a group biography of Bloomsbury, and a project of criticism that invigorates still life as a visual key to the interpretation of the domestic lives of the artists. One might call it still life beside itself, or the domestic interior for the age of metadata. The basic observation is unassailable: these artists were living and working in unusual and radical domestic configurations, and so the visual environments pictured in their work bridge the practice itself with the life around it. Another way of describing the modernist mode.

In This Dark Country, Rebecca’s observations are always striking. Often they are elucidating; sometimes they seem to be reaching, and yet when they are reaching they are also at their most creative. She calls her form of close reading “overreading,” after Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and says she is “more interested in possibility than proof.” This, I think, is where the creative possibilities of criticism come into play, where criticism can be more than biography, and where the reading of a critic might open up new windows into the work, and for the work into the world. And this, after all, is why we write criticism to begin with.

On the cover is a detail from the Dora Carrington painting Tulips in a Staffordshire Jug (1921), in which Rebecca identifies two tulips “attempting to distance themselves from the rest of the bouquet,” leaving behind “intimations of disappointment, need and discord.” She goes on to connect the composition to her lover Ralph Partridge and the triangulation of their relationship within Bloomsbury. As a reader, you have to learn a lot about the biography before you can begin to see anything in the paintings other than genre and technique. In my generation we are sadly inured to the spiritual life of a still life with flowers.

Studying theory and criticism in college, we learned to be suspicious of the biographical fallacy, of the idea that the narrative of an artist’s life might help us understand his or her work in any meaningful way. We should start from the work itself, we learned, and from its reception in the world, and never take the original artifact as illustrative of an external reality. For the past 25 years, literature has been so dominated by autofiction that it has become as natural as breathing. This is not the case in contemporary art. Despite diversions into things like new sincerity and identity art, art has largely tried to preserve a further layer of mediation, even distance—to cling to the position of the critic rather than the artist.

Anna Kornbluh would disagree: in her book Immediacy she argues that the immersive installation as a medium is cut from the same cloth as social media and memoir. I counter that immersive experiences are far enough from the central thrust of what artists are actually doing to undercut this line of thinking. I also wonder if the act of interpretation that Kornbluh wants to see happening, the work of critical engagement, might actually be taking place immanent to the surely self-conscious authorship of much of this culture supposedly opposed to mediation.

Frances Lindemann, writing in The Drift, takes inventory of autocriticism in the literary field: Emily Van Duyne on Sylvia Plath, Rebecca Mead on George Eliot, Jenn Shapland on Carson McCullers, Joanna Biggs on nine women writers. She describes the problem:

Three distinct but related types of identification are at play in this genre, which we might call auto-criticism: the author’s personal identification with a character, her identification with the writer at hand, and her identification of that writer’s life with her work. (This last type is also known as biographical criticism.)

Rebecca Birrell’s biography of Bloomsbury does not reach into memoir, other than in brief asides that mention her research in the first person, but I almost wonder if that might further enrich it. Rather than trying to get rid of mediation, this winking inclusion of the author for me can celebrate the relational nature of the twinned acts of writing and reading. Frances concludes her argument:

Auto-criticism, and its identificatory principle in particular, is most fundamentally flawed in its false understanding of the directionality of reading.

When we willfully misread art or literature, we accept that we are seeing our reflection in the glass along with whatever we are looking at. We recognize that we cannot possibly imagine ourselves in the exact circumstances of the artist—and that we would not want to even if we could, because the whole point of art is to somehow speak across time, across subjectivities, from your universe into mine. Reading is a multi-dimensional practice. We create new dimensions with every reading. When we peer through a frame and into another plane of being we see an act of imagination tied to a real person in a real place and time, and we—real too in our own place and time—must commit another act of imagination. And this makes it no less real. It resonates back and forth, sometimes forever.

What I have learned from Rebecca Birrell is that there are interesting things to learn out there, and archival research plus a trained eye can unearth stories that enrich our readings of art. This is a creative act, and the stories that resonate with us have as much to do with us as they do with the artists.

My mother is visiting Taipei this week and while we were browsing moom bookshop I picked up a copy of The Bloomsbury Cookbook. She is here to spend a couple days with me after a week looking after my daughter while I was away on business at the art fair in Hong Kong. Paging through recipes from Charleston as we recover from a meal of oden and Czech wine, the importance of domesticity, of cooking and eating together, of a good interior, of a communal energy could not be more obvious. In the case of Bloomsbury, the radical impulse comes right up against the domestic appetite, and they are seen to live not in opposition but in harmony, bound up together. I am learning to see in a still life with tulips the whole world we are trying to build around us. I am learning to map it out in an omelette and a loaf of bread.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

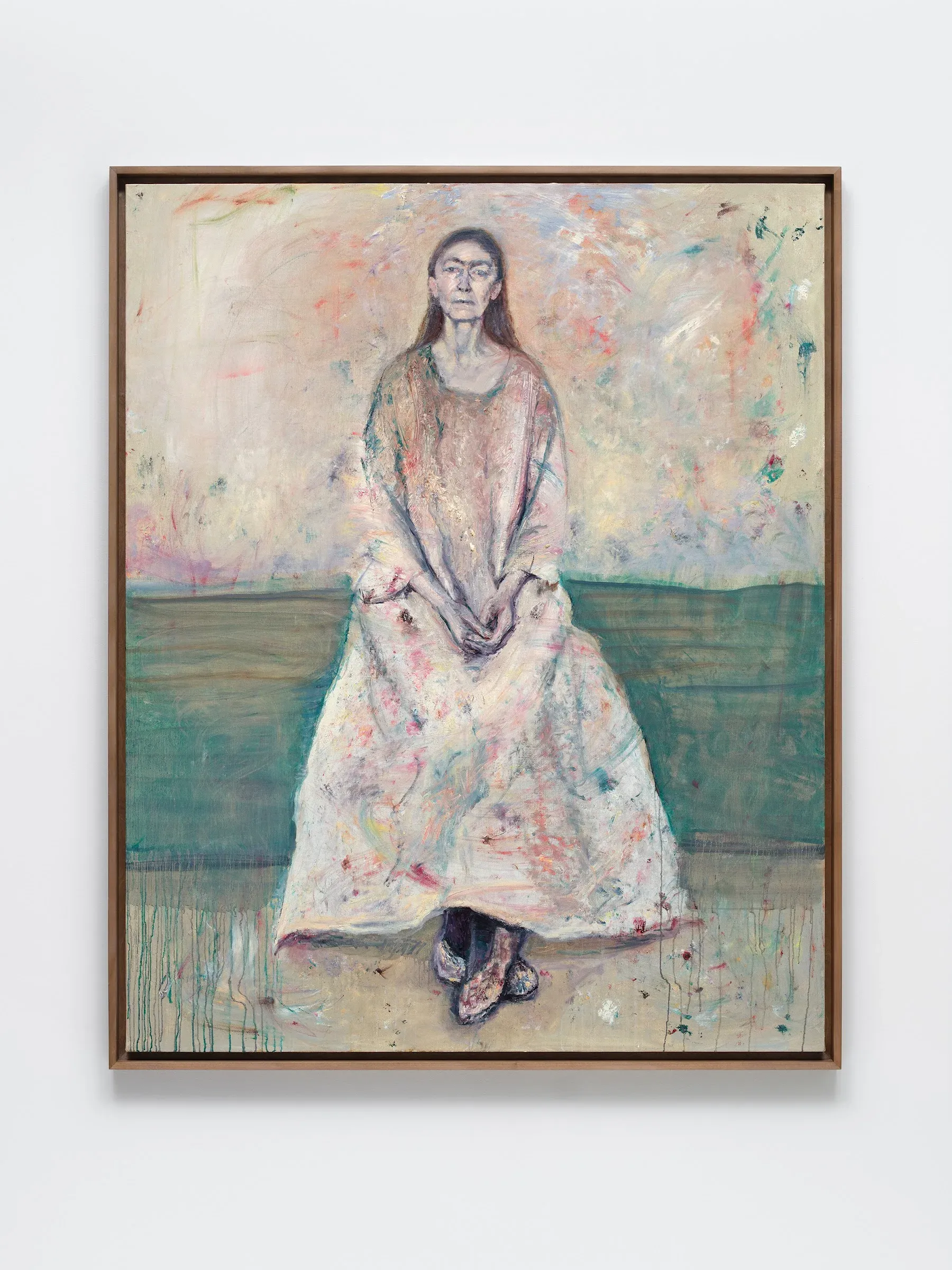

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s profile of Celia Paul, like most of the press she gets, leads with a visit to her flat in London. Based on the descriptions that her interlocutors and interviewers share, it sounds like a theatrically sparse place, a minimally viable configuration of chairs and bed frames that provides just enough surfaces to sit on and gaze into the mid-distance, just enough windows through which to notice a corner of a roof or the branch of a tree, and just enough bare walls against which to lean paintings. Just enough of a space, in other words, for one to focus on the twin projects of looking and being looked at, which she has made the core of her blessedly old-fashioned practice as a painter—a painter of the sort who paints the things in front of her. Knausgaard writes of how he understands her work:

… their distinctive combination of weightlessness and heaviness. The physical, material world that they depicted seemed light in some peculiar way, while their emotional presence was always heavy: the paintings were grounded in feelings. Usually it is the other way around, isn’t it, the material world has weight, and the inner, the spiritual, the abstract are light, and ungraspable, really.

And he might as well be speaking the language of Asle, of the “luminous darkness” that our fictional artist seeks in his paintings. When Jon Fosse (speaking through Asle) writes of how it is only at the darkest moments “when the darkness starts to shine,” this is not only a metaphor for finding the grace of forgiveness and acceptances when the going gets tough; this is very literally how Asle is making his compositions, turning his lights off and looking at them in the gloom of the Arctic dusk, looking for a strength and brightness that he puts onto canvas through overpainting and underpainting. Through the materiality of the painting, Asle incorporates the spiritual sense of the ineffable into landscapes, moments, and portraits. This is what Knausgaard is suggesting here: it’s the light that’s heavy. He comments specifically on Celia Paul’s series of paintings of chairs. She explains herself:

I think my chair paintings are self-portraits. I have two identical chairs: one is in my studio—my models sit on it—and this one, the one that I paint, is in the room where I sleep.

Knausgaard on the same chair paintings:

We see not the chair in itself, as that is for sitting on, but the moment it represents, the here and now it lifts forth. Not the world, but our connection to the world. … Shouldn’t someone have been sitting in that chair? In a strange way, the absence of a person reveals another presence, for, though the room is certainly empty, it vibrates with life, and it does so because someone sees it, and that someone exists in the painting, in its colors and shapes.”

Immediately I think of the twin chairs of Septology, one for Asle and one for his late wife, the presence who haunts his home studio and all corners of his life. She, too, was a painter, though as his career progressed and hers stalled she turned inward and focused on icon painting. We cannot tell if she became a contemporary artist interested in icons or if it was purely a hobby so, although she didn’t seem to exhibit widely, I choose to again hold this contradiction loosely and think of her icons as doing what Asle’s paintings do, reflecting back the light in the darkness.

Asle is a rugged individualist of an artist. Though he begrudgingly accepts the companionship of his neighbor and his namesake, his time in the studio is pure solitude. By way of company, he sits and fixes his gaze on a specific portion of the sea. The other chair must remain empty. Celia Paul’s practice, on the other hand, is a profoundly social one. Her work is all about connection. Across the decades, she paints her mother, her sisters, her son, her lover and his friends—all in the same chair, within the same four walls. Her connections to these people matter. That chair glows with the presence of a life lived to the fullest. Knausgaard:

It is easy to think art that leans toward the autobiographical is first and foremost a representation of things or events. But the essential fact about art is that it is an event in itself. It is something that comes into being.

Celia Paul’s Bloomsbury studio, where she has lived since 1982, was a gift from Lucien Freud, her lover, tutor, and portraitist. The space itself, the framework, the walls that surround the chairs, are a part of the practice of living, of loving, of modeling, of painting that she constructed in relationship to him. She has spoken openly of how her work found a new dimension of freedom after he died. Much has been said about their relationship, the degree to which it defines or does not define her work, the extent to which it was positive or healthy or anything else. I’m not sure much of that matters, in that it’s less about that particular relationship and more about the fact of relationship, the field of social connection in which she has chosen to pursue her painting. This is what makes her work so very much of our time. Now in her 60s, Celia has become known for her writing in addition to her painting, and she speaks eloquently on the back-and-forth between these two ways of working:

It is a way of articulating thoughts that otherwise just brew. That can work evocatively in painting. But with words, you need to have order of a different kind. One sentence does have to follow another.

It was her memoir Self-Portrait and the more recent Letters to Gwen John that opened my eyes to the field of connection that underlies her painting practice. Letters, in particular, I find one of the most beautiful meditations there is on how we understand art as a part of life, on how art draws from life and in return gives a sense of shape back to it. In Gwen John, Celia sees a parallel life from another pocket in time—a namesake who lived nearly a century before her.

Like Celia, Gwen John studied at the Slade. Like Celia, Gwen John entered into a relationship with an older artist, and their affair became a defining aspect of how she related to art and to the world. In Celia’s letters, we get a sense of how she goes about her day to day, how she thinks about her paintings, but we also get to look at Gwen John’s work, and at Rodin and their milieu, with fresh eyes. Gwen John’s portraits, particularly her self-portraits, printed alongside Celia Paul’s, are revelatory—modern. And yet:

Gwen never tried to paint Rodin and she made no pencil sketches of him. He was her ‘Maitre’ and she was so overwhelmed by him that she wouldn’t have been able to work from him. … She wanted Rodin to look at her, but she didn’t feel able to return his gaze.

In her newest body of work, Celia’s paintings have taken on something of the religious icon for me, as much as they have also absorbed the social portraiture of Freud. In the press release for the new exhibition, “Colony of Ghosts,” her practice is described as “looping back and forth through time to the people and places closest to her. … Constancy and change, and how the past is always held in dialogue with the eternal present of the painted image, are, for Paul, inextricably linked to a consideration of self.” We see in these images a field of space-time that is turned into light, a living and breathing field of life that comes through every object, every surface, every wrinkle on every face, every knuckle on every hand. Reaching into her own past, like Asle:

My young self and I—we are the same person. I can stretch out my old hand—with its age spots—and hold my young unblemished hand.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

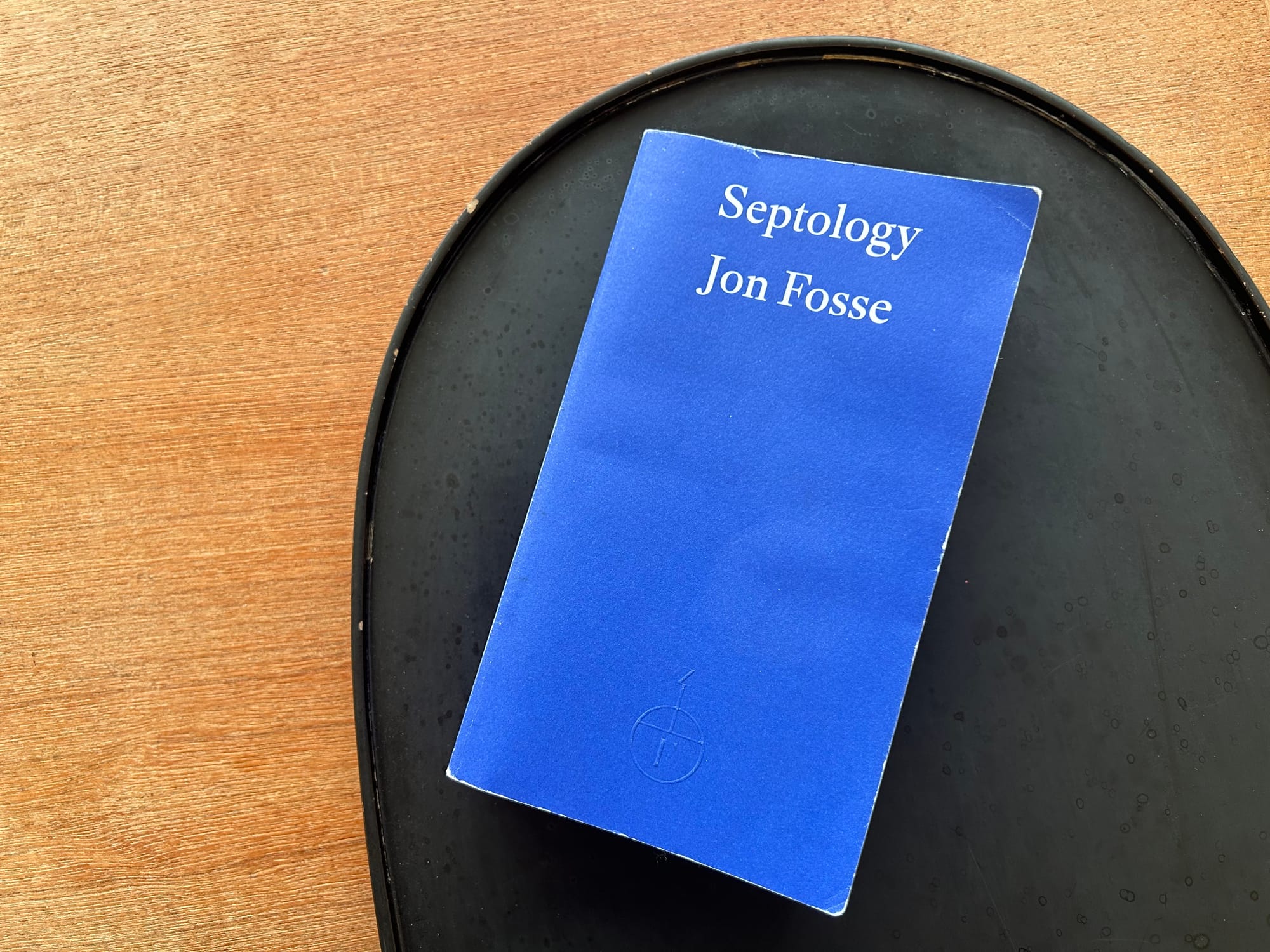

When you finish reading a book like Septology, the impulse is to reach out immediately: to cast about on the internet, to message friends, to wedge it into conversations, to write something down, to figure out what’s sticking in your mind and then compare notes to understand if your experience of the book is coming from inside the book itself or from mythical status of the book.

From what I can tell of my casting about, most people think that Septology is about god. Asle, the aging painter who narrates the novel in his stream of consciousness, falls asleep each night—closing each of the seven volumes of the story—somewhere in the process of moving along his rosary beads, either in the Lord’s Prayer or Salve Regina or Ave Maria or one of those other bits of sacred ritual that have been sadly abandoned in the churches that I grew up in. When he speaks about god, however, he is very clear that he doesn’t believe in god at all, at least not in the traditional “old-man-in-the-sky” conception of god. Asle feels the presence of god in two places: in the love and connection he cultivated with his late wife, and in the creative process of painting that he has spent a lifetime pursuing. To quote William Blake:

Every thing that lives is holy.

Septology contains some of the best descriptions I’ve read of how art functions in the life and mind of the artist. Not all artists, of course, but some of them, and particularly those who remain committed to the modernist idea of art that spans the long twentieth century, bound up with the practice of calling a self into being. With all of the connections between light and the divine that Jon Fosse weaves through his writing on painting, particularly the “luminous darkness,” at a certain point in my reading I started picturing Asle’s work in the key of Celia Paul. Until I started reading her writing, I did not get her work at all. I lacked the capacity to understand not only her work, but probably an entire strand of contemporary art (this same one that I refer to here, the one committed to or at least growing out of the modernist idea of art: individual and spiritual and craftsmanlike, bookended between an earlier institutional aesthetics of ritual, what modernism struggled against, and a later institutional aesthetics of bureaucracy, which art has become). I could not have read Septology without having first read Celia Paul.

Partway through Septology, I was shocked and gratified to see that Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose blurb sits prominently on the back of my thick Fitzcarraldo edition of the book (“Jon Fosse is a major European writer”), had authored a new essay on Celia Paul, published in the New Yorker and in a MACK monograph to accompany her forthcoming Victoria Miro solo exhibition. Shocked because I did not expect such a literal connection to be manifested into reality, at least not so quickly; gratified because it always feels so predictably good to have my intuitions confirmed or at least paralleled by minds much greater than mine; and then also maybe a little bit mortified, because the timing was all a little bit too perfect, and I wondered if I had perhaps seen a reference to this forthcoming essay and somehow started visualizing Celia’s paintings within Asle’s narrative.

Septology is about the multiverse. Asle seems like a thoroughly wholesome widower, still married in deed and mind to the late love of his life: when his neighbor sits down in her chair, untouched these ten years, his reaction is visceral. As he drives between his home and the city, where he buys groceries and art supplies and delivers paintings once a year to his gallery, he continually encounters phantom versions of himself. He sees himself young and falling in puppy love with his wife; he sees the two of them moving into their first home outside the city (they too, in nested flashback, notice his car driving by). But he also encounters another version of himself, not these shadows of his own past but a present-day alternate reality self, another painter named Asle drinking himself to death. We learn that the two Asles met when they were still teenagers, and have gone through life aware of one another, as the wholesome Asle moves from triumph to triumph in his career and in his marriage, while the shadow Asle suffers through the dissolution of marriages entered too easily, the instability of finances never given a chance to get going, and ultimately the lonely descent into drinking the dark days away.

The beauty of first-person narrative, the beauty of this way of telling so many different stories at once, is that we as readers have profound access to the protagonist Asle’s painting. He starts every morning considering the canvas that he is working on, a purple line and a brown line intersecting to form a cross, and we learn about where his paintings come from, how he started painting pastoral scenes from his rural village and then quickly learned to paint out of his mind particular images or moments that stuck with him in his observations of the everyday. He narrates at length the way that light shapes his process: “the pictures I paint in spring and summer have to wait until autumn or winter before I can really see them, yes, in the darkness, yes, I need to see pictures in the dark to see if they shine, and to make them shine more, or better, or truer, or however it’s possible to say it, anyway the picture has to have the shining darkness in it.” Then, when he paints a portrait, which he does rarely—one portrait of his wife sits leaning against a chair in his attic; he also paints his neighbor’s sister sight unseen as a Christmas present—we see Celia Paul. I am incapable of imagining these pictures as anything else. They sit so clearly in my mind that I fear their dark luminosity will be burned into my eyelids.

And yet, a bit weirdly, we have no conception of what the other Asle’s paintings might look like. We read about his work only during the time when light Asle and dark Asle first meet: dark Asle is living in a basement and sleeping with a pub waitress, and they are introduced by a mutual drinking buddy. They bond over a mutual resistance to painting the kinds of anodyne pastoral scenes that people from their villages are willing to buy. This is all we learn of dark Asle’s work; it is like he represents an arrested development in the process of artistic growth. Light Asle has already started moving on, but dark Asle feels bound by circumstance to keep churning them out: he sells his pictures for beer money on the steps of the pub. And yet, it is dark Asle who is first accepted to art school, and dark Asle who implicitly gives light Asle permission to leave high school early to pursue this track. We never see dark Asle’s work again.

A lot of doubling and doppelganging is happening in culture right now. In both Severance and The Substance, the public self and the private self struggle over agency. We share one body and, perhaps, one soul, but choice and chance conspire to create circumstances that splinter our realities. The work of love is the work of reconciliation. You are one. God is in the darkness:

It’s in the hopelessness and despair, in the darkness, that God is closest to us, but how it happens, how the light I get clearly into the picture gets there, that I don’t know, and how it comes to be at all, that I don’t understand … it’s definitely true that it’s just when things are darkest, blackest, that you see the light, that’s when this light can be seen, when the darkness is shining, yes, and it has always been like that in my life at least, when it’s darkest is when the light appears, when the darkness starts to shine, and maybe it’s the same way in the pictures I paint, anyway I hope it is

Septology is not a morality tale. Hero Asle and shadow Asle are not two choices that a person can make—righteous choices do not lead to mystically good ends, and dissolute choices do not drag one down into despair. The two Asles are one and the same, fundamentally and inextricably bound together. How this works within the universe of the book, I have no idea. I choose to read it at a distance, to allow these paths and routes to wrap around one another and intersect as they choose. As a reader, I hold this contradiction loosely, like the composition of the painting that opens each chapter:

two lines that cross in the middle, one brown and one purple, and I see that I’ve painted the lines slowly, with a lot of thick oil paint, and the paint has run, and where the brown and purple lines cross the colours have blended beautifully and I think that I can’t look at this picture any more