Essay: Real Paintings and Fictional Painters (Part I)

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

When you finish reading a book like Septology, the impulse is to reach out immediately: to cast about on the internet, to message friends, to wedge it into conversations, to write something down, to figure out what’s sticking in your mind and then compare notes to understand if your experience of the book is coming from inside the book itself or from mythical status of the book.

From what I can tell of my casting about, most people think that Septology is about god. Asle, the aging painter who narrates the novel in his stream of consciousness, falls asleep each night—closing each of the seven volumes of the story—somewhere in the process of moving along his rosary beads, either in the Lord’s Prayer or Salve Regina or Ave Maria or one of those other bits of sacred ritual that have been sadly abandoned in the churches that I grew up in. When he speaks about god, however, he is very clear that he doesn’t believe in god at all, at least not in the traditional “old-man-in-the-sky” conception of god. Asle feels the presence of god in two places: in the love and connection he cultivated with his late wife, and in the creative process of painting that he has spent a lifetime pursuing. To quote William Blake:

Every thing that lives is holy.

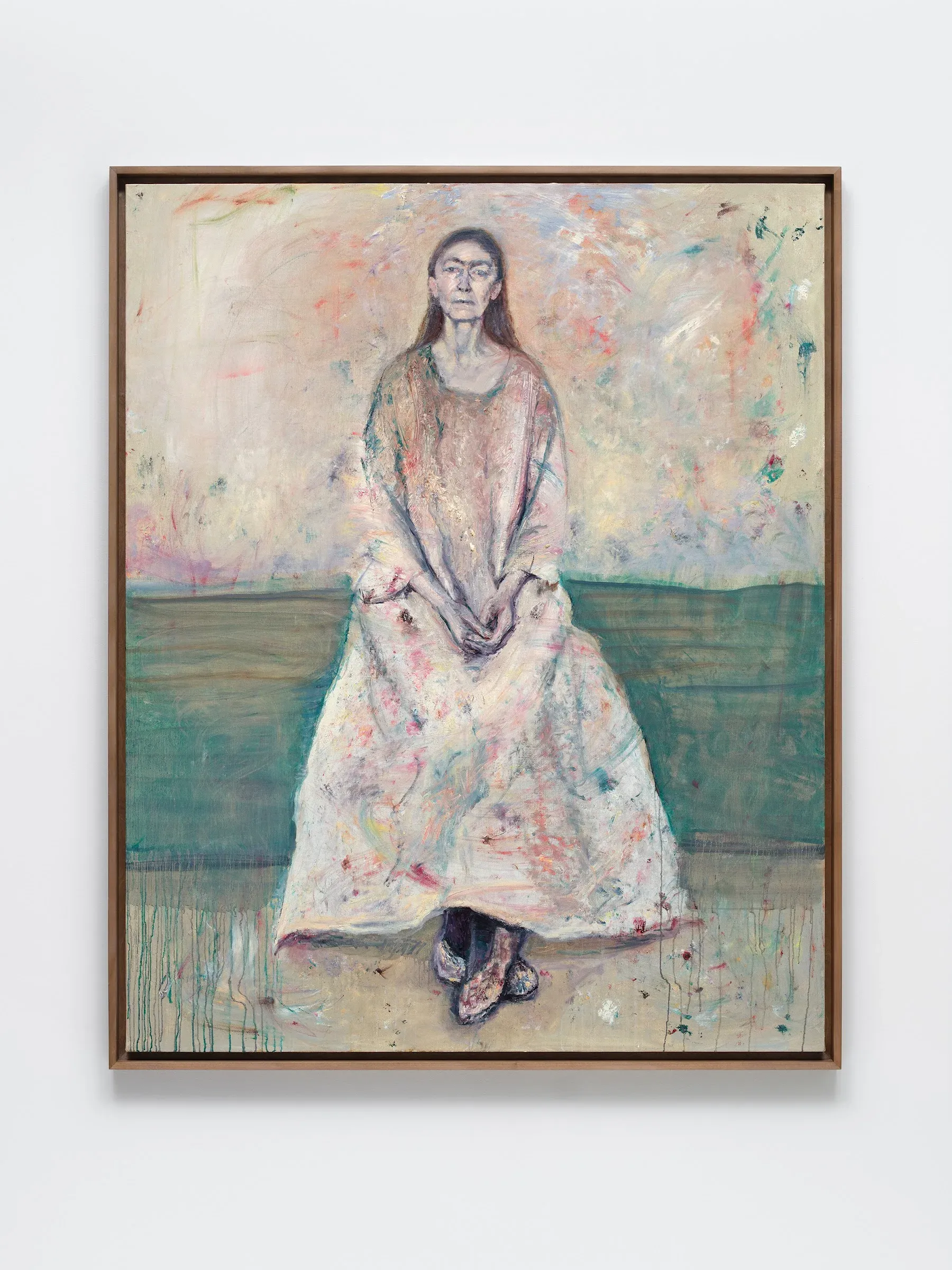

Septology contains some of the best descriptions I’ve read of how art functions in the life and mind of the artist. Not all artists, of course, but some of them, and particularly those who remain committed to the modernist idea of art that spans the long twentieth century, bound up with the practice of calling a self into being. With all of the connections between light and the divine that Jon Fosse weaves through his writing on painting, particularly the “luminous darkness,” at a certain point in my reading I started picturing Asle’s work in the key of Celia Paul. Until I started reading her writing, I did not get her work at all. I lacked the capacity to understand not only her work, but probably an entire strand of contemporary art (this same one that I refer to here, the one committed to or at least growing out of the modernist idea of art: individual and spiritual and craftsmanlike, bookended between an earlier institutional aesthetics of ritual, what modernism struggled against, and a later institutional aesthetics of bureaucracy, which art has become). I could not have read Septology without having first read Celia Paul.

Partway through Septology, I was shocked and gratified to see that Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose blurb sits prominently on the back of my thick Fitzcarraldo edition of the book (“Jon Fosse is a major European writer”), had authored a new essay on Celia Paul, published in the New Yorker and in a MACK monograph to accompany her forthcoming Victoria Miro solo exhibition. Shocked because I did not expect such a literal connection to be manifested into reality, at least not so quickly; gratified because it always feels so predictably good to have my intuitions confirmed or at least paralleled by minds much greater than mine; and then also maybe a little bit mortified, because the timing was all a little bit too perfect, and I wondered if I had perhaps seen a reference to this forthcoming essay and somehow started visualizing Celia’s paintings within Asle’s narrative.

Septology is about the multiverse. Asle seems like a thoroughly wholesome widower, still married in deed and mind to the late love of his life: when his neighbor sits down in her chair, untouched these ten years, his reaction is visceral. As he drives between his home and the city, where he buys groceries and art supplies and delivers paintings once a year to his gallery, he continually encounters phantom versions of himself. He sees himself young and falling in puppy love with his wife; he sees the two of them moving into their first home outside the city (they too, in nested flashback, notice his car driving by). But he also encounters another version of himself, not these shadows of his own past but a present-day alternate reality self, another painter named Asle drinking himself to death. We learn that the two Asles met when they were still teenagers, and have gone through life aware of one another, as the wholesome Asle moves from triumph to triumph in his career and in his marriage, while the shadow Asle suffers through the dissolution of marriages entered too easily, the instability of finances never given a chance to get going, and ultimately the lonely descent into drinking the dark days away.

The beauty of first-person narrative, the beauty of this way of telling so many different stories at once, is that we as readers have profound access to the protagonist Asle’s painting. He starts every morning considering the canvas that he is working on, a purple line and a brown line intersecting to form a cross, and we learn about where his paintings come from, how he started painting pastoral scenes from his rural village and then quickly learned to paint out of his mind particular images or moments that stuck with him in his observations of the everyday. He narrates at length the way that light shapes his process: “the pictures I paint in spring and summer have to wait until autumn or winter before I can really see them, yes, in the darkness, yes, I need to see pictures in the dark to see if they shine, and to make them shine more, or better, or truer, or however it’s possible to say it, anyway the picture has to have the shining darkness in it.” Then, when he paints a portrait, which he does rarely—one portrait of his wife sits leaning against a chair in his attic; he also paints his neighbor’s sister sight unseen as a Christmas present—we see Celia Paul. I am incapable of imagining these pictures as anything else. They sit so clearly in my mind that I fear their dark luminosity will be burned into my eyelids.

And yet, a bit weirdly, we have no conception of what the other Asle’s paintings might look like. We read about his work only during the time when light Asle and dark Asle first meet: dark Asle is living in a basement and sleeping with a pub waitress, and they are introduced by a mutual drinking buddy. They bond over a mutual resistance to painting the kinds of anodyne pastoral scenes that people from their villages are willing to buy. This is all we learn of dark Asle’s work; it is like he represents an arrested development in the process of artistic growth. Light Asle has already started moving on, but dark Asle feels bound by circumstance to keep churning them out: he sells his pictures for beer money on the steps of the pub. And yet, it is dark Asle who is first accepted to art school, and dark Asle who implicitly gives light Asle permission to leave high school early to pursue this track. We never see dark Asle’s work again.

A lot of doubling and doppelganging is happening in culture right now. In both Severance and The Substance, the public self and the private self struggle over agency. We share one body and, perhaps, one soul, but choice and chance conspire to create circumstances that splinter our realities. The work of love is the work of reconciliation. You are one. God is in the darkness:

It’s in the hopelessness and despair, in the darkness, that God is closest to us, but how it happens, how the light I get clearly into the picture gets there, that I don’t know, and how it comes to be at all, that I don’t understand … it’s definitely true that it’s just when things are darkest, blackest, that you see the light, that’s when this light can be seen, when the darkness is shining, yes, and it has always been like that in my life at least, when it’s darkest is when the light appears, when the darkness starts to shine, and maybe it’s the same way in the pictures I paint, anyway I hope it is

Septology is not a morality tale. Hero Asle and shadow Asle are not two choices that a person can make—righteous choices do not lead to mystically good ends, and dissolute choices do not drag one down into despair. The two Asles are one and the same, fundamentally and inextricably bound together. How this works within the universe of the book, I have no idea. I choose to read it at a distance, to allow these paths and routes to wrap around one another and intersect as they choose. As a reader, I hold this contradiction loosely, like the composition of the painting that opens each chapter:

two lines that cross in the middle, one brown and one purple, and I see that I’ve painted the lines slowly, with a lot of thick oil paint, and the paint has run, and where the brown and purple lines cross the colours have blended beautifully and I think that I can’t look at this picture any more