Essay: Real Paintings and Fictional Painters (Part III)

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

Portraiture for me has become a practice of autofiction. When I started my career, I was obsessed with technology and bored by painting. I was undereducated and under-informed, and have only learned a little bit since then. A lot of my writing and thinking in the first decade of my career was on what we called post-internet art, which Karen Archey and I defined as contemporary art “consciously created in a milieu that assumes the centrality of the network.” A key point of reference for us was David Joselit’s idea of painting beside itself; I remember Karen telling me about a dream in which she titled an exhibition “Everything Beside Itself.” Up to a certain moment, the only painting that made sense to me was conceptual in nature, playing with the codes of digital culture to make painting about its own production. Following David: Jutta Koether, Wade Guyton, Seth Price. Serious and impersonal painting.

Through approaches to portraiture like Celia Paul’s, I have slowly come to understand how every painting stands beside itself, how the social diagram of the production of art is actually visualized in many kinds of painting, if not most, and acknowledging this reality is, in fact, one of the primary directives of looking at and talking about art. In her current exhibition in London, Celia recomposes a famously staged photograph of Lucien Freud, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, and Michael Andrews out to lunch in Soho in 1963. This is not a biographical anecdote. This is painting fully beside itself. There is zero distance between Celia’s Colony of Ghosts and Jana Euler’s “GWF (Great White Fear)” paintings.

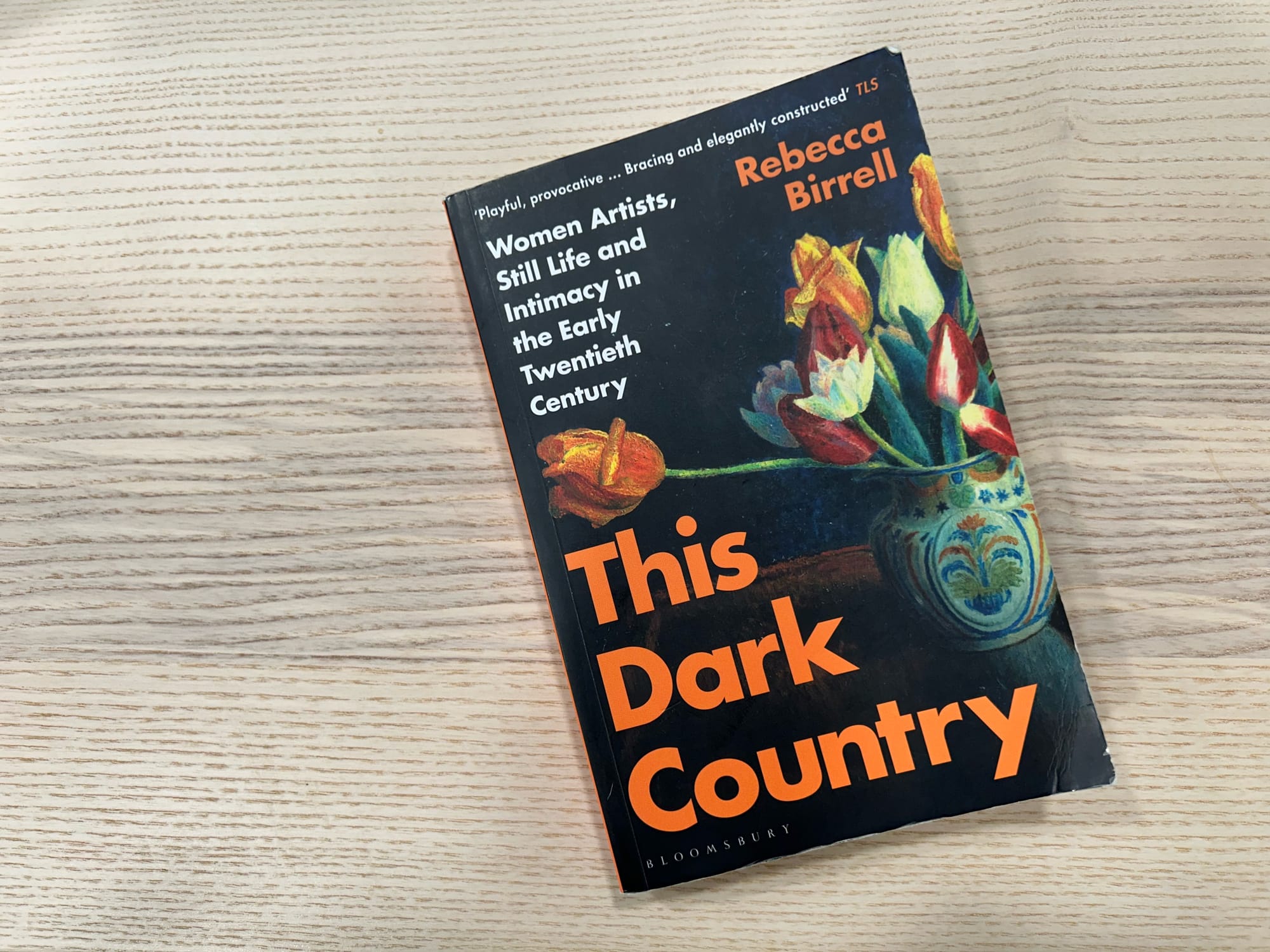

At the London Review Bookstore a few years back I picked up a copy of This Dark Country, a striking book by the curator and scholar Rebecca Birrell that has become enormously important to me. Subtitled Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century, it is something of a group biography of Bloomsbury, and a project of criticism that invigorates still life as a visual key to the interpretation of the domestic lives of the artists. One might call it still life beside itself, or the domestic interior for the age of metadata. The basic observation is unassailable: these artists were living and working in unusual and radical domestic configurations, and so the visual environments pictured in their work bridge the practice itself with the life around it. Another way of describing the modernist mode.

In This Dark Country, Rebecca’s observations are always striking. Often they are elucidating; sometimes they seem to be reaching, and yet when they are reaching they are also at their most creative. She calls her form of close reading “overreading,” after Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and says she is “more interested in possibility than proof.” This, I think, is where the creative possibilities of criticism come into play, where criticism can be more than biography, and where the reading of a critic might open up new windows into the work, and for the work into the world. And this, after all, is why we write criticism to begin with.

On the cover is a detail from the Dora Carrington painting Tulips in a Staffordshire Jug (1921), in which Rebecca identifies two tulips “attempting to distance themselves from the rest of the bouquet,” leaving behind “intimations of disappointment, need and discord.” She goes on to connect the composition to her lover Ralph Partridge and the triangulation of their relationship within Bloomsbury. As a reader, you have to learn a lot about the biography before you can begin to see anything in the paintings other than genre and technique. In my generation we are sadly inured to the spiritual life of a still life with flowers.

Studying theory and criticism in college, we learned to be suspicious of the biographical fallacy, of the idea that the narrative of an artist’s life might help us understand his or her work in any meaningful way. We should start from the work itself, we learned, and from its reception in the world, and never take the original artifact as illustrative of an external reality. For the past 25 years, literature has been so dominated by autofiction that it has become as natural as breathing. This is not the case in contemporary art. Despite diversions into things like new sincerity and identity art, art has largely tried to preserve a further layer of mediation, even distance—to cling to the position of the critic rather than the artist.

Anna Kornbluh would disagree: in her book Immediacy she argues that the immersive installation as a medium is cut from the same cloth as social media and memoir. I counter that immersive experiences are far enough from the central thrust of what artists are actually doing to undercut this line of thinking. I also wonder if the act of interpretation that Kornbluh wants to see happening, the work of critical engagement, might actually be taking place immanent to the surely self-conscious authorship of much of this culture supposedly opposed to mediation.

Frances Lindemann, writing in The Drift, takes inventory of autocriticism in the literary field: Emily Van Duyne on Sylvia Plath, Rebecca Mead on George Eliot, Jenn Shapland on Carson McCullers, Joanna Biggs on nine women writers. She describes the problem:

Three distinct but related types of identification are at play in this genre, which we might call auto-criticism: the author’s personal identification with a character, her identification with the writer at hand, and her identification of that writer’s life with her work. (This last type is also known as biographical criticism.)

Rebecca Birrell’s biography of Bloomsbury does not reach into memoir, other than in brief asides that mention her research in the first person, but I almost wonder if that might further enrich it. Rather than trying to get rid of mediation, this winking inclusion of the author for me can celebrate the relational nature of the twinned acts of writing and reading. Frances concludes her argument:

Auto-criticism, and its identificatory principle in particular, is most fundamentally flawed in its false understanding of the directionality of reading.

When we willfully misread art or literature, we accept that we are seeing our reflection in the glass along with whatever we are looking at. We recognize that we cannot possibly imagine ourselves in the exact circumstances of the artist—and that we would not want to even if we could, because the whole point of art is to somehow speak across time, across subjectivities, from your universe into mine. Reading is a multi-dimensional practice. We create new dimensions with every reading. When we peer through a frame and into another plane of being we see an act of imagination tied to a real person in a real place and time, and we—real too in our own place and time—must commit another act of imagination. And this makes it no less real. It resonates back and forth, sometimes forever.

What I have learned from Rebecca Birrell is that there are interesting things to learn out there, and archival research plus a trained eye can unearth stories that enrich our readings of art. This is a creative act, and the stories that resonate with us have as much to do with us as they do with the artists.

My mother is visiting Taipei this week and while we were browsing moom bookshop I picked up a copy of The Bloomsbury Cookbook. She is here to spend a couple days with me after a week looking after my daughter while I was away on business at the art fair in Hong Kong. Paging through recipes from Charleston as we recover from a meal of oden and Czech wine, the importance of domesticity, of cooking and eating together, of a good interior, of a communal energy could not be more obvious. In the case of Bloomsbury, the radical impulse comes right up against the domestic appetite, and they are seen to live not in opposition but in harmony, bound up together. I am learning to see in a still life with tulips the whole world we are trying to build around us. I am learning to map it out in an omelette and a loaf of bread.